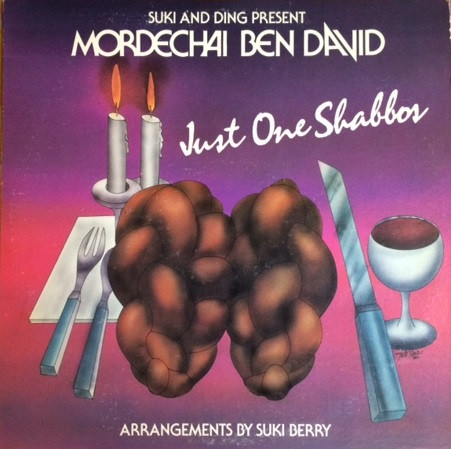

July 26, 2023|ח' אב ה' אלפים תשפ"ג Just One Shabbos

Print Article

One of the English-language Jewish songs with the most staying power is Mordechai Ben David’s “Just One Shabbos.” Dovid Nachman Golding tells the story of when and why it was first written and produced:

On one of our trips to Eretz Yisrael in the early ’80s, MBD and I would be amazed by Rabbi Meir Schuster ztz”l. Every Friday night, he would place at least dozens, and up to hundreds, of young Jews who had never experienced a true Shabbos meal with a family in a warm, frum environment. During that trip, we were working on a Shabbos album, and it didn’t take MBD long to write the lyrics and the tune to this amazing hit song (“Western Wall on Friday night / His first time ever there / Strapped into his knapsack / With his long and curly hair…”).

My good friend Stanley Felsinger was the owner of Camp Monroe, a camp for Jewish children from nonreligious backgrounds. Soon after Stanley opened the camp, he himself became Torah-observant, which led him to make the entire camp kosher. He then took it a step further and approached Rav Aaron Schechter of Yeshiva Chaim Berlin and asked him for a suggestion on how to deal with Shabbos in camp. The Rosh Yeshivah suggested that Stanley try to get the children to experience some part of Shabbos, so Stanley came up with an idea of forming a volunteer Shabbos Club. But how would he attract the children to join this club? Then an idea hit him. Every Friday, he would play the song “Just One Shabbos” over the camp loudspeakers.

It didn’t take long before the entire camp learned the song and started signing up for the club. When Stanley repeated this story to me, I passed it along to MBD. It blew MBD’s mind that hundreds of children were singing his song, and they weren’t even religious! That was all the information he needed to hear. Several hours later, we drove up to Camp Monroe with a few musicians — I remember that Yossi Piamenta a”h was one of them. Mordechai did a free concert for the entire camp, and the place was really rocking to the music. What a memorable night that was — it taught me never to underestimate the power of a popular song when it comes to igniting the spark in a Jewish neshamah.

“Just One Shabbos” is a fantastic song and clearly an inspiring and impactful one, and perhaps its source is a Gemara in Talmud Yerushalmi (Taanis 3a): אִילּוּ הָיוּ יִשְׂרָאֵל מְשַׁמְּרִין שַׁבָּת אַחַת כְּתִיקֻּנָהּ מִיַּד הָיָה בֶן דָּוִד בָּא

Chazal in Talmud Bavli, however, teach us that it is not just one Shabbos, but rather it takes two for us to go free and bring the geulah. The Gemara (Shabbos 118a) tells us:

אמר רבי יוחנן משום רבי שמעון בן יוחי אלמלי משמרין ישראל שתי שבתות כהלכתן מיד נגאלים

If only the Jewish people would observe two Shabbosos they would immediately be redeemed.

Rav Mendel of Vitebsk explains that the Gemara doesn’t refer to keeping just any two Shabbosos. Rather, it means if the Jewish people would observe Shabbos chazon, the week before Tisha b’av, and Shabbos Nachamu, the week after it, Moshiach would come.

If we used the week of Chazon to feel the pain, mourn the loss, acknowledge the shortcomings, and commit to improve, and we then observe Shabbos Nachamu, in which we take comfort from our resolve to translate those emotions into actions that will improve our behavior, then surely we will have the means to transform the condition of Jewish existence.

The question is - where do we find this nechama? How does reading the words “Nachamu nachamu ami” this Shabbos make anything different? Where is the nechama when nothing is different and nothing has changed? Israel continues to have enemies that seek her annihilation. Antisemitism continues to be on the rise. People continue to confront challenges and suffering. Where is this elusive nechama?

Rav Pinkus points out that nechama is not about getting back what we lost. When we pay a shiva call and offer nichum aveilim, we cannot bring the deceased back to life. If we could return someone or something lost to the person who lost it, they wouldn’t need nechama, they would have what they were desperate for back. So what, then, is nechama?

An answer can be found in an ancient and mysterious text called Perek Shira. Many believe that it was written by Dovid HaMelech after he completed the book of Tehillim. Perek Shira is discussed by many of our greatest sages including the Ramban. It lists 84 elements of the natural world including the sky, the earth, and all kinds of animals and shows how the natural world sings God’s praises by attributing a pasuk to each one. The message of this magnificent work is that the whole world is a symphony, and we can learn from what each aspect of the world contributes to God’s song.

Perek Shira states: “Retzifi omeir: nachamu nachamu ami, yomar Elokeichem.” The Retzifi is a certain type of bird and through its song and its life we learn something about nachamu nachamu ami. What does this cryptic statement mean? What does the Retzifi do and what did Dovid HaMelech mean to suggest about what we can learn from it?

The Knaf Renanim, written by the great 17th c. Moroccan Kabbalist, Rabbi Avraham Azulai, explains that this bird lives in the north and does not like the cold. Other species of birds fly south for the winter, but the Retzifi stays behind because he does not want to miss the beginning of the spring. So how does this species of bird survive the cold and harsh winter?

Rav Azulai explains that they form a tight circle there. Each bird puts its head under the feathers of the one next to it. The Retzifi survives the winter and stays warm only by connecting with his fellow birds. Remarkably coordinated, these birds take care of themselves by finding cover and simultaneously provide cover for the one next to them under their wing. It is from this behavior that we learn the meaning of Nachamu nachamu ami.

According to this interpretation, Dovid HaMelech was suggesting that if we want to know how to weather the cold, survive the darkness, and endure through the harsh exile, we must follow the model of the Retzifi. Survival, and indeed nechama, comfort, are all about practicing achdus - unity and togetherness. If we confront our challenges with empathy, kindness, and a desire to draw closer together, we will not only survive, but we will thrive.

Yes, nothing is different one week later than it was on Tisha Bav. Nothing has changed about our circumstances or our standing in the world. And yet, there is one thing different. Through sitting on the floor together, through crying on one another’s shoulder and through feeling each other’s pain we become closer, more cohesive, and more of a people.

That is the comfort that Yeshayahu promised. Nachamu, nachamu ami…if you feel a sense of ami, my united people, if this hardship brings you closer instead of driving you farther apart, then indeed, nachamu nachamu, you have found comfort despite the difficulty.

When Tisha B’Av ends, we rise up off the floor and anticipate a return to music, meat, clean laundry, and joy. But when doing so, we must not put the pain of others in the rearview mirror. The nechama comes if it remains in our windshield, a continued concern for us to work on and help.

Just one Shabbos of inviting those who are alone, reaching out to those who are different than us, making an effort to say good Shabbos to everyone we pass, and we will finally all be free.