April 27, 2023|ו' אייר ה' אלפים תשפ"ג All You Need is Love

Print Article

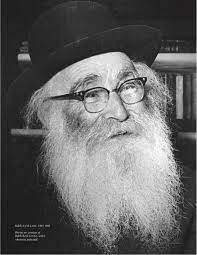

Rav Aryeh Levin was known as the tzadik of Yerushalayim, the righteous man of Jerusalem. He was incredibly pious, kind, and a great scholar. He lived in the quaint area of Nachlaot, right behind the shuk in Machaneh Yehudah. There was a young man who grew up in the neighborhood whom R’ Aryeh knew well but he felt the boy was avoiding him. One day, they bumped into each other in the narrow alleys of Nachlaot and Rav Aryeh confronted him and said, “I can’t help but feel you are avoiding me, tell me how are you?” The young man sheepishly replied that it was true, he was avoiding the great rabbi as he had grown up observant but had chosen to walk away from observant life altogether.

He said, “Rebbe, I was so embarrassed to meet you since I have taken off my kippa and am no longer observant.” Rav Aryeh took the young man’s hand into his own and said the following. “My dear Moshe. Don’t worry. I am a very short man. I can only see what is in your heart, I cannot see what is on your head.”

Our Parsha commands us V’ahavta l’reiacha kamocha, to love our neighbor as ourselves. “Kamocha” doesn’t mean love your neighbor as you love yourself, which is unrealistic, if not impossible. It means love you neighbor—why? Because “Kamocha,” he or she is similar to you. You both possess the same spark of life, the same Godly soul, you both have strengths and weaknesses, you both have virtues and faults, you both have things to be proud of and areas to work on.

We cannot love others, certainly not all others as much as we love ourselves, but we certainly can learn to love more. Why should we and how can we? Kamocha, because if you can cut away their different kippa or their lack of a kippa, if you ignore how they dress differently, act differently, think differently, if you cut away their idiosyncrasies and habits that drive you crazy, you will find they are kamocha, just like you.

Rebbe Akiva witnessed thousands of his students fail this lesson. They focused on their differences rather than choose to embrace their similarities and the result was that they couldn’t see themselves in one another, they could not relate or identify. They saw their fellow student as different, the other, and that caused them to disrespect one another. Rebbe Akiva attended thousands of funerals and delivered thousands of eulogies as his students were cut down by a punitive plague and he turned around and taught, ואהבת לרעך כמוך is the כלל גדול בתורה, the primary principle of the Torah.

It is not a coincidence that the same Rebbe Akiva is quoted in Pirkei Avos as teaching us חביב אדם שנברא בצלם, precious is every person because we were all created in the image of God. Internalizing that is the secret of loving everyone.

We may not have the capacity to love others as much as ourselves, but we can do a whole lot better at loving others, especially those who are different than us, by focusing on the Kamocha, that as different as they seem, they are in truth just like us. Loving those who are just like you in hashkafa, halacha and are your dear friends is wonderful but it is not the most authentic expression of ahavas yisroel. Peeling back the layers of that which separates us from others until we find common ground and that which connects us, that is ahavas yisroel.

But love goes beyond tolerating, it goes beyond finding commonality. To truly love a fellow Jew means something even more.

R’ Moshe Leib Sassover used to tell his chassidim that he learned what it means to love a fellow Jew from two Russian peasants. Once he came to an inn, where two thoroughly drunk Russian peasants were sitting at a table, draining the last drops from a bottle of strong Ukrainian vodka. One of them yelled to his friend, “Do you love me?” The friend, somewhat surprised, answered, “Of course, of course I love you!” “No, no”, insisted the first one, “Do you really love me, really?!” The friend assured him, “Of course I love you. You’re my best friend!” “Tell me, do you know what I need? Do you know why I am in pain?” The friend said, “How could I possibly know what you need or why you are in pain?” The first peasant answered, “How then can you say you love me when you don’t know what I need or why I am in pain.”

R’ Moshe Leib told his chassidim, he learned from these peasants that truly loving someone means to know their needs and to feel their pain. Real love is not lip service, it is not just tolerating one another. Love is noticing someone is having a bad day, it is feeling their pain, it is showing someone you care, even when that person is someone you barely know or don’t know at all.

The blessings of Birchos HaShachar are said in the plural – פוקח עורים, מלביש ערומים, etc. There is one exception – שעשה לי כל צרכי thank you God, who fulfills all of my needs. Why is this blessing written in the singular?

The same R’ Moshe Leib Sassover who taught us what it means to love a fellow Jew explains that when it comes to ourselves, we should have an attitude that I have everything I need. We should feel content and satisfied. However, when it comes to others, we must be thinking – he or she don’t have everything they need. What are they lacking? How can I help them? What can I do for them?

There are people around us hurting, lacking or in pain. If we claim to love them, we cannot fail to notice. While Shabbos is the happiest most peaceful day of the week for many, for others, it is filled with stress, anxiety, and pain. Imagine being alone and each week as you get closer to Shabbos wondering if you will get invited out for meals. Imagine coming to shul still not having dinner or lunch arranged and wondering if anyone, even those who “love” you, will make sure you have a place to go or will give you greater dignity by inviting you earlier in the week. Imagine the prospect of a long Shabbos day by yourself. How much of a nap and how much reading can you do before you feel lonely? If we love our fellow Jews and our neighbors, we must make sure none of them feels alone.

In the sefer Kavanas Ha’Ari, it says that before beginning davening in the morning, one should say: הריני מקבל עלי מצות ואהבת לרעך כמוך, I hereby accept upon myself the positive commandment to Love your fellow as yourself.” Based on R’ Moshe Leib Sassover’s insight, we can understand this to mean that before we can pour out our hearts to Hashem for all of our needs, we must pause to think about our fellow man and their needs. Before we ask Hashem to be there for us, we must commit to be there for others.